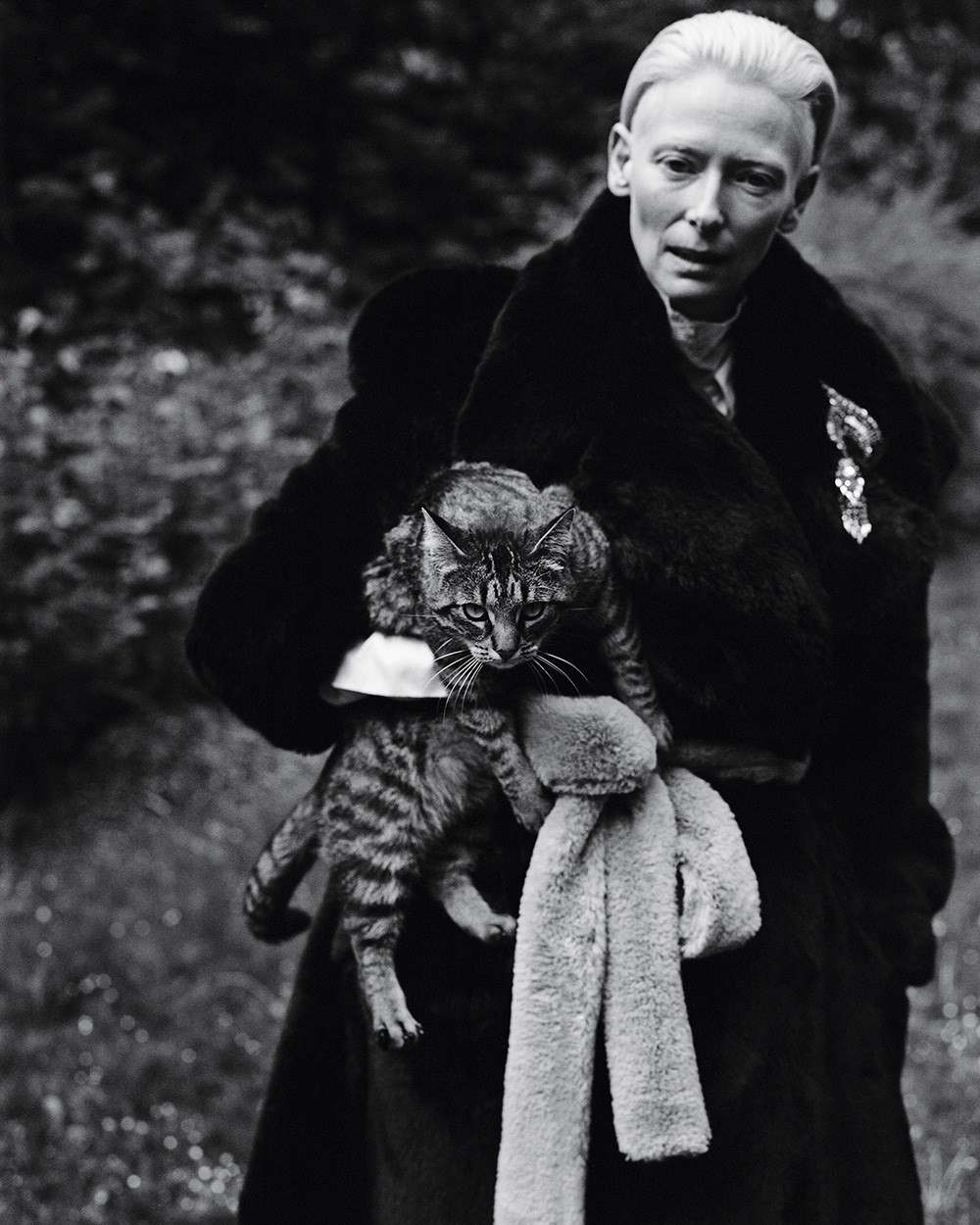

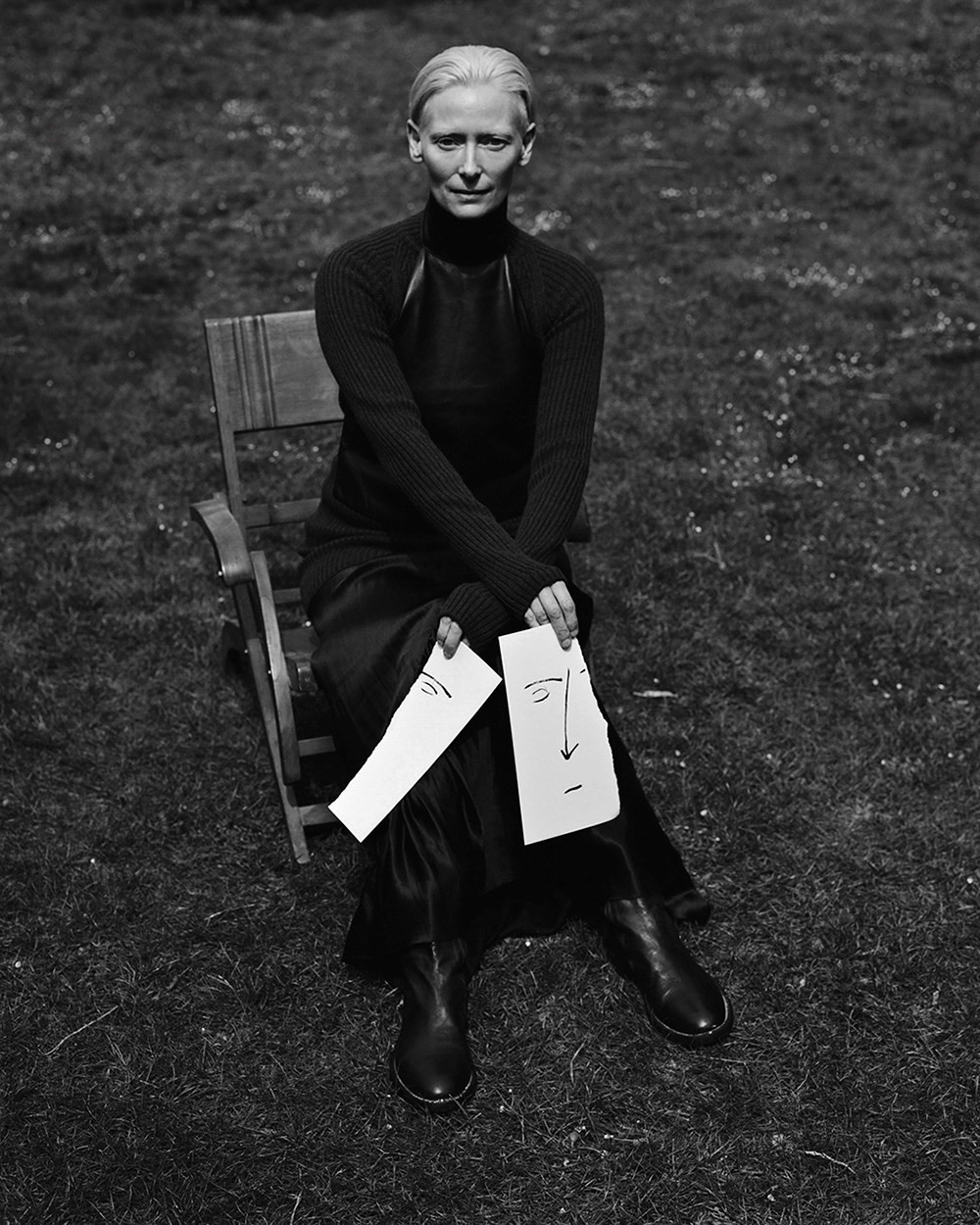

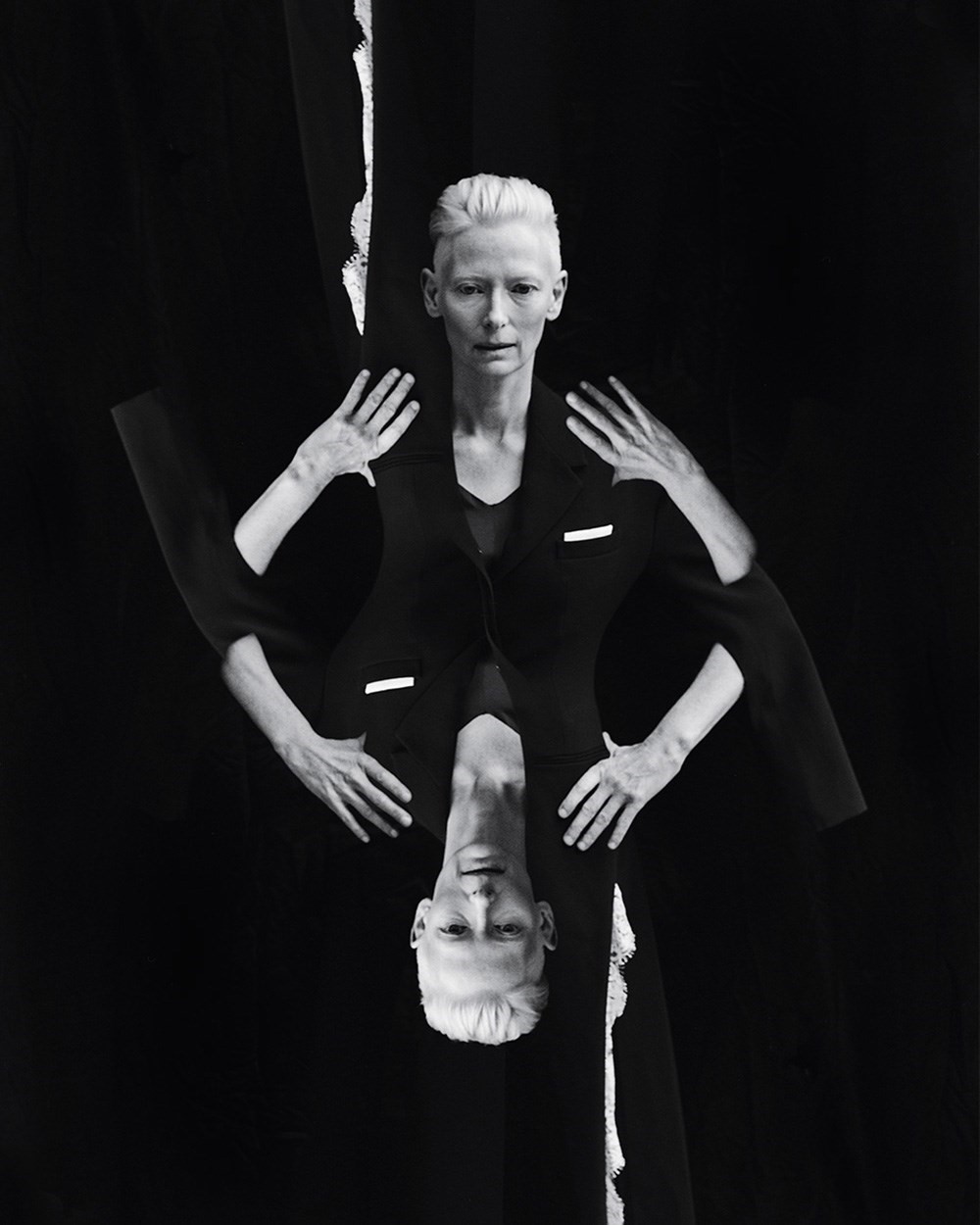

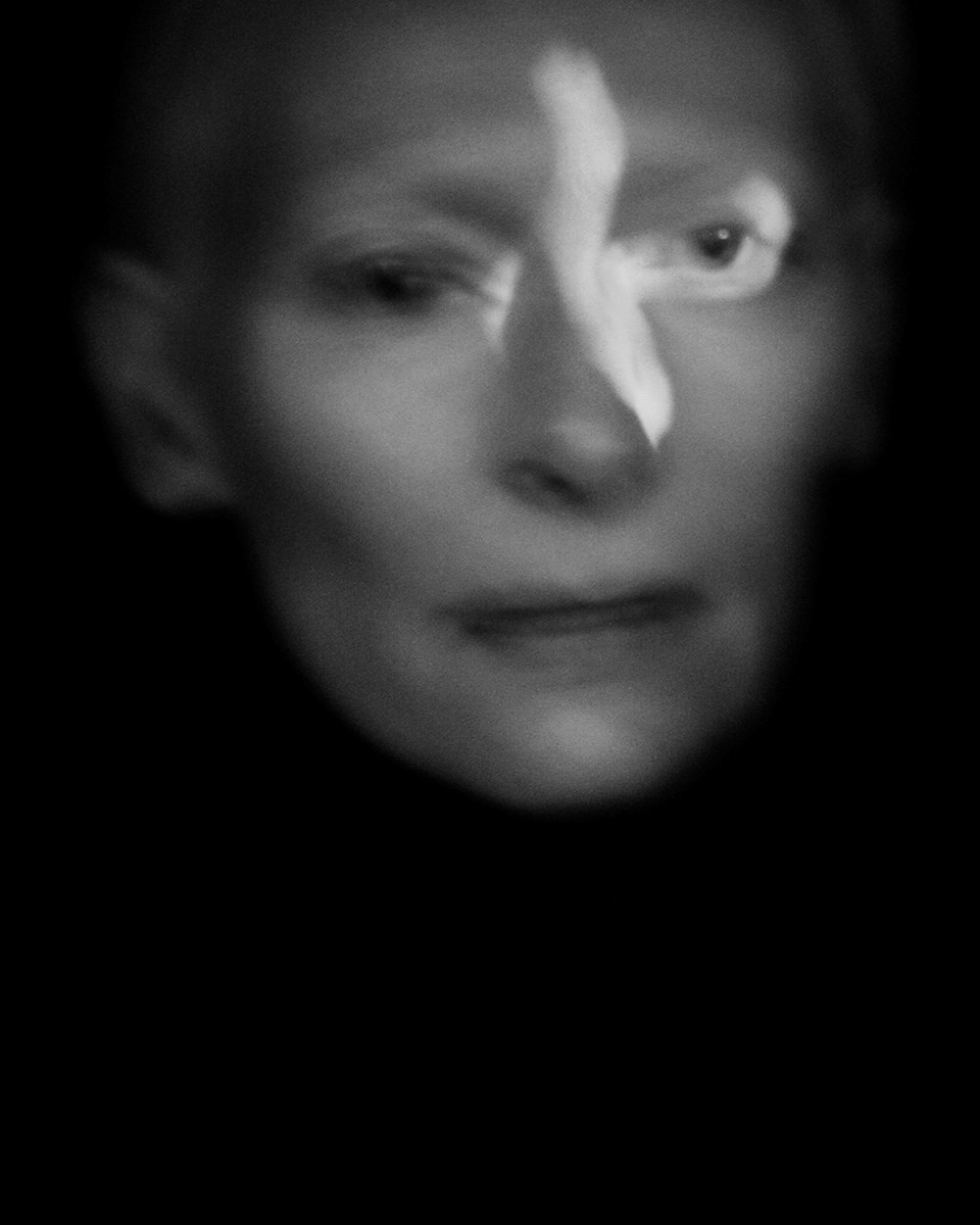

As the smiling face of depraved CEOs everywhere, Tilda Swinton excels in fantasy epic Okja – and makes her case for the art of caricature as exquisite weapon

In her new film, Okja, Tilda Swinton makes you laugh at how hysterical she is, hate her and pity her – all within the crack of a forced smile. Her performance as Lucy Mirando, the new CEO of Mirando Corporation, is astonishing. Then, just as you’re aware how much you’re revelling in her egregiousness, it hits you – we can all recognise this twisted archetype. They might be an old boss (I couldn’t possibly comment) or the clownish, deadly new model of politician, shameless in engineering alternative facts.

Mirando Corporation is not nice, but Lucy is hellbent on rebranding it as such. Her father manufactured napalm and caused people’s skin to fall off. Her sister blew up a lake. So, in her delusional quest for approval, Lucy reinvents the meat industry with 26 ‘super pigs’, exported to farmers globally and raised over a period of ten years – before the best is sent back to the US for a parade. Okja, you’ll gather from the title, is the perfect specimen. Of proportions that’d make a hippo look diminutive, the pig was raised in the South Korean mountains with a young girl, Mija (Ahn Seo-hyun, another brilliant performance), as her companion. And Mija, despite being a child going up against a huge multinational, is not going to let Mirando claim her best friend.

Raising questions about what happens when an animal becomes dinner, and when the labs think they know better than nature – you’ll have to watch – director Bong Joon-ho finds light in this potentially dark material, thanks to a script co-written with The Men Who Stare at Goats author Jon Ronson. You can bet Jake Gyllenhaal, as out-of-control media personality Dr Johnny Wilcox, had a great time in the role, and Paul Dano as Animal Liberation Front lynchpin Jay is the cool, calm TCB activist who will make you want to shop for a new suit afterwards – the man has discipline and style.

As seen at this year’s Cannes, Okja could end up being the last Netf lix movie to enter the competition (French law states films shown in the cinema cannot be screened on television for three years afterwards, whereas Netflix is the grande dame of the streaming revolution).

That would be a shame, since the California heavyweight produces some truly imaginative, out-there cinema that others are unwilling to take a chance on, from Beasts of No Nation to Ava DuVernay’s Oscar-nominated documentary 13th. And the world needs plenty of that, whatever screen you’re watching.

In a way, the less you know about Tilda Swinton, the better, not only because she doesn’t play by the same rules as everyone else – she lives in the Scottish Highlands and is entirely absent from social media – but because she has a history of inhabiting otherworldly roles, in films that take in fantasy and myth. But, just because it wouldn’t feel right to be exhaustive with Swinton, you can’t help but want to open the door and let a little light in. You get the feeling you can really learn from her. She is as compelling as her art, which extends far beyond cinema.

What were you channelling for the part of Lucy Mirando? Her character is very contemporary – she could be a politician or social media star from 2017.

Tilda Swinton: Lucy is a properly modern version of a pretty worn old construct: the classic narcissist currently vibrantly fashionable every-which-where. She has consciously put herself together – ‘Brand Lucy’ – according to her desire to be super- media-friendly, bright and shiny, certified organic, trustworthy, popular, adorable, future-bound. She is a liar, straight-up, but she wants to be loved. You don’t have to go far to trip over myriad examples among our media-dependent contemporaries. Some follow the profile pretty closely, actually – one in particular popped into our consciousness long after we conceived Lucy and her look: another famous and powerful daughter, child-blonde hair, expensive teeth, cutting a public style that’s part-Barbie doll-demure, part-spa manager, part-high priestess…

What as a character does she tell us about humanity? Do you think people will see her as a warning?

TS: I think there is something very powerful in a time like ours – when thinking people are grasping for a foothold in reasonable and considered response, (and) many leaders appeal to the lowest aspects of our human nature – about a satire broad and extreme enough to go beyond the bounds of our worst fears. A year ago, Lucy would have seemed way more outlandish and buffoonish than she seems now. When director Bong (Joon-ho) and I went about putting together the portrait of Mason for Snowpiercer (Swinton plays a ruthless politician in Joon-ho’s dystopian thriller from 2013), we wanted to create a grotesque, a melting of the most baroque bombast of all the political monsters we could think of: Hitler, Mussolini, Gaddafi, Thatcher, Berlusconi. Mason is a clown, broad and over-the-top. But, honestly, Trump, Le Pen, Farage and this new style of Caligula-complex bully tops Mason with regularity.

Vanity, ignorance and mean-spiritedness do not occupy nuanced landscapes: they need to be called out and their ridiculous posturings exposed in order to offer some moral clarity. We need what Jonathan Coe calls ‘a rough and ready, cartoonish shortcut to the truth… The present moment calls for absurdism, caricature and tomfoolery, because these are the only ways to capture our current reality.’

Lucy’s recognisability is key. She’s not, actually, much unlike people we can all name. We hope that, once people have seen her trying to sell Mirando as an ethical saviour conglomerate, they may be less taken in by her very visible – non- fictional – fellow con artists ogling for our trust, support and votes, and be diligent in searching for the humane alternatives.

Is Lucy consciously a bad person? Or is it more complex than that?

TS: I think we have to go beyond looking to label people as good and bad: Lucy is as complex a human being, as are we all. Brought up on the knee of a monstrous father, locked in deadly sibling rivalry with her sister, from whom she is determined to be different and more triumphant in every way, her liberal arts education gives her the tools to look like something reliably healthy and benign. She knows the talk to talk and the walk to walk. She is planning her glory – like her straightened teeth – over a span of years. But for all that, her fatal f law is her essential disconnection from humane compassion and any sense of social responsibility. She is damaged at the core, no doubt. If she truly wanted to be different from her family without still being attached to the dependence on capital and all that that entails, she might have escaped becoming a monster like them, albeit in a different guise.

When reading a script, are you more attracted to a part if it feels comfortable or totally alien?

TS: Honestly, it’s not that often I encounter a part for the first time in a script. I more usually know a project before it ever gets written down. The first connection for me is with the filmmaker or artist I’m working with, then, secondly, with the project. The idea of what I might play is pretty much always a third issue, approached once my alignment with the piece of work as a whole is established. So, with Okja, for example, Bong showed me a tiny sketch he made of a girl and a big pig, about three years before we started shooting, and I was working on the film as a producer for quite a while before the script was even started. So, the question of what I might play, and whether it falls near or far from the tree in terms of ‘dress up and play’ for me is really quite a light matter.

Sometimes, of course, people call me out of the blue and (invite me) to join in on something I don’t have to be a part of setting up, something that tickles my fancy for some reason, and it’s a delight to take a holiday into another world for a spell. I suppose it’s a wee bit like asking someone if they prefer going to a party in fancy dress or as themselves: both have their advantages and both have their different challenges. It’s really a trip to have them both as options regularly on offer.

You’ve worked with some visionary talents whose work champions a kind of fantastical approach – people like Jim Jarmusch, Terry Gilliam and, most recently, Wes Anderson. What attracts you to these directors?

TS: All of those people you mention are not only artists I have admired from afar for years, whose work has inspired and energised not only the filmmaking but the entire culture of our time, but I am proud and happy to say they are all friends, whom it is one of the most profound honours of my life to be able to call comrades. They all make work that inhabits entirely unique and identifiable worlds – maybe the highest achievement for any artist – built on a combination of exquisite eye, visionary sense of atmosphere and properly righteous heart. To be a part of their dreamscapes is exactly the sort of good fortune that keeps me interested in making films.

You star in the Suspiria remake later this year. What can you say about your part in the film – and were you always a fan of Argento’s hyper-colourised surrealism?

TS: Suspiria is a film Luca Guadagnino and I have talked about making a ‘cover’ of for years. We are dyed-in-the-wool fans of Dario Argento’s classic and we’re happy to be in the middle of completing our film. We shot in Italy and Berlin over the winter (and are) now cutting. I play Veva Blanc, a highly respected choreographer and director of the Markos Dance Company. The film is a universe of dance and magic and the radical politics of 70s Berlin. We shot with a cast of 38 women – including the great Ingrid Caven, Mia Goth, Renee Slouterdijk, Angela Winkler, Dakota Johnston, Chloë (Grace) Moretz, Sylvie Testud and the wonderful Jessica Harper, who starred in Argento’s original – and three men: filmmaker Fred Kelemen, photographer Mikael Olsson and psychoanalyst Lutz Ebersdorf. It’s going to be wild and very much its own animal.

You’re a Hollywood actress but your other life is in Scotland. Could you function without this balance? Which is the escape and which is reality?

TS: It’s funny to see myself described as a Hollywood actress, since I spend so little of my life in America or making films there. But it is true, I have probably done more of both than most people who live where I do. My life is a pretty harmonious weave of home and away, although more and more the former these days. I have always worked from home – most of my work, whether it’s pre- or post-production, takes place there. The telephone, Skype and FaceTime are household gods for facilitating this pattern. Shooting is always the shortest part of making a film, certainly the films I make.

I try to lure people up to the Highlands to cut down on me flying back and forth. Generally, they are only too happy to come: a walk on the beach and any work conversation accompanied by four springer spaniels seems all the sweeter. But I love to travel, just as I love returning home after a journey – the variation in our life is something for which I am always grateful. Neither here nor there is escape: both are adventures of particular colours and feed each other. Life without an element of journeying is unimaginable, although the journeys can be close or far from home.

The Scottish Highlands are one of the last great wilderness landscapes we have. It is a privilege to live here.

Regarding movies and lifestyle, do you think you have more of a personal dichotomy than other actors? Have you ever felt pressured to be more mainstream – or is the notion of a mainstream a toxic idea?

TS: I think what’s toxic is the notion that there is only one mainstream. As we all know particularly sharply these days, one man’s mainstream is another man’s deep leftfield… Vive la difference.

I don’t really know what other actors’ lives are like, (and) I wouldn’t want to speculate. But, certainly, living outside of a big city, as I have done for the past 20 years, makes for a very particular relationship with the work I do that, I sense, manages to cut out all sorts of backwash that people who make films living in cities might have to contend with. I live and I work and I don’t have a presence in the world beyond those two practical and present realms. I also have zero social media presence – never have had any – which leaves more space and time for collecting eggs and shooting the breeze and thinking about building a boat and all that good stuff.

You can hear your own ears where I live. You can wake up and make a plot for your day and follow as much of it as you wish.

The possibility of being blown off course is always present, but being hijacked by the agendas of others is less of a challenge in the country. It’s possible to be quiet here. This, I cherish.

Would you say you’re a curious person?

TS: Most certainly curious. Powered by curiosity above most things, I’d say. That, and a nose for any opportunity within which I can, for as prolonged a period as possible, say to my good friends at the end of a day, ‘See you tomorrow.’

What’s the last big question you asked yourself?

TS: A question of two parts that I’ve asked myself constantly over the past 30 years: who am I and how must I live?

Do you have habits? Is there one form of creation you take part in every day?

TS: Whenever possible, I work in my garden. If away from it, I daydream about my plans for it.

Why?

TS: Because it is one of the most life-grounding things one can do, to work with the land, plant seed and tend plants. Eating from your own harvest is more satisfying than very many good things. (It’s) truly creative, collaborative – a dialogue with nature, from the earth to the weather and the insects that help along the way – please try it if you haven’t yet. A window-box can be a psychedelic kingdom.

What’s your chief characteristic?

TS: Idleness and a readiness to be amused.

What’s the last thing you laughed at?

TS: Ruprecht the Monkey Boy in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels.

What does that say about your sense of humour?

TS: You tell me…

TILDA SWINTON

TEXT DEAN MAYO DAVIES

PHOTOGRAPHY JACK DAVISON

STYLING ROBBIE SPENCER

DAZED & CONFUSED, SUMMER 2017